Deep down, I happen to be very shallow.

– Pat Paulson

This is different than ctrl+C right?

Definitely so. If we were asked to copy one object from one place to another place, I guess we might have sought help from ctrl+c and ctrl+v. However, when we ask(programmatically) python to do it; it is done in a different way and that is what we will discuss next.

So, what is this all about?

Let’s assume you are writing a python module that runs indefinitely. It populates a master list of items frequently and calls different methods with a reference to this list as an argument. The expectation is, the methods will perform their intended task with the passed reference and the master list can meanwhile keep on receiving more data.

Something which might look like this:

populate_master_list(master_list)

list_ref = master_list

ThreadPool(max_workers=8).submit(operate_on, list_ref)

populate_master_list(master_list)

Sounds normal, right?

Well, not exactly.

What happens when a method is invoked and starts working with the given list reference separately, The changes made on the reference will reflect on the main list?

most importantly, do we want this behavior?

What if we do not have enough space at our disposal, hence can not support additional copies?

Many questions can appear here, and trust me that is where the concept of deep copy and shallow copy comes in.

Going by the definition,

A shallow copy means constructing a new collection object and then populating it with references to the child objects found in the original. In essence, a shallow copy is only one level deep. The copying process does not recurse and therefore won’t create copies of the child objects themselves.

And

A deep copy makes the copying process recursive. It means first constructing a new collection object and then recursively populating it with copies of the child objects found in the original. Copying an object this way walks the whole object tree to create a fully independent clone of the original object and all of its children.

Now, let us understand it with some examples.

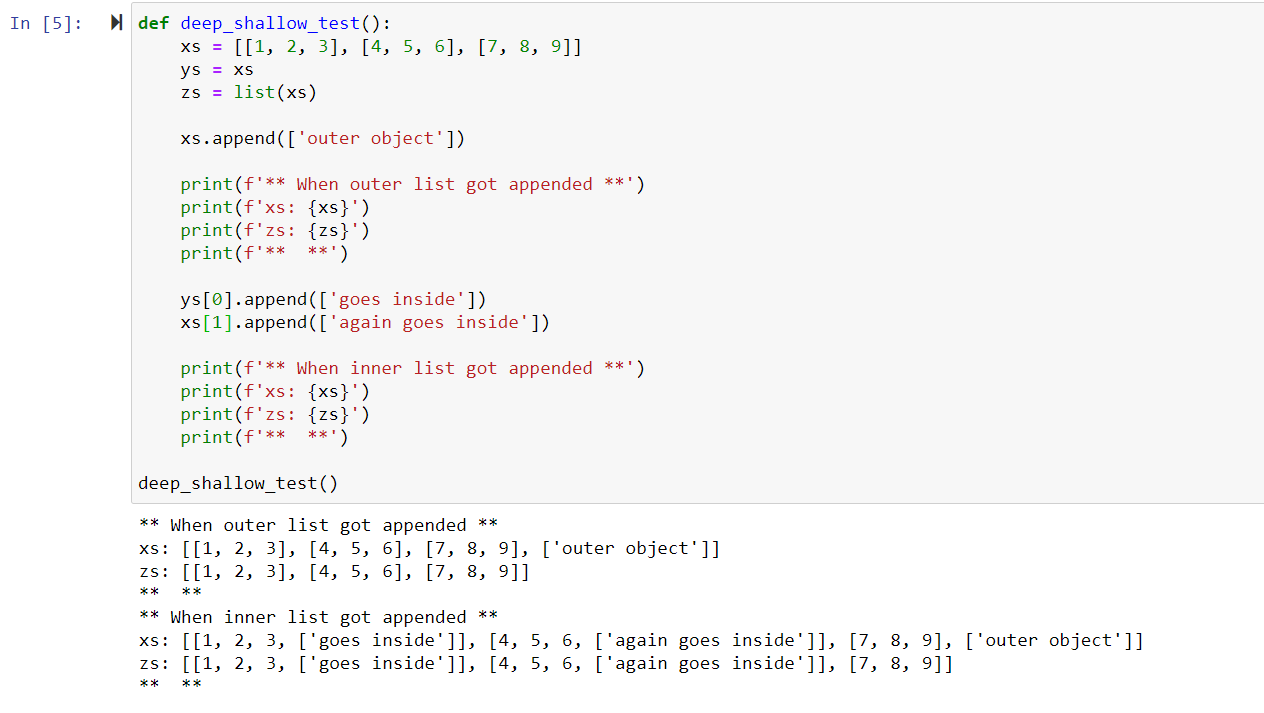

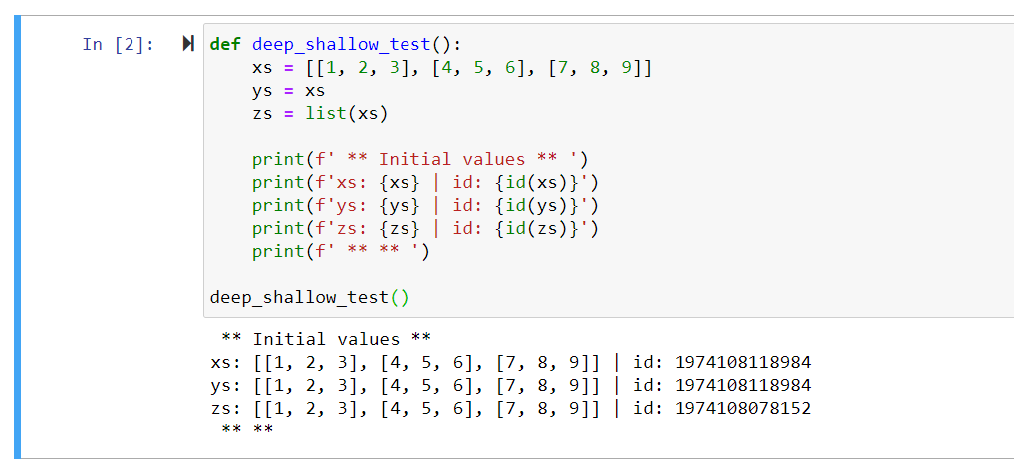

In deep_shallow_test(), xs is a list of lists, and ys and zs both got a copy of xs. A copy but a different copy each. Technically speaking, if xs is a label assigned to the list of lists objects then so is ys. They both are two different names assigned to a single person. That is why exactly the values returned by their id()s are the same.

However, the third assignment, i.ezs = list(xs)

is what we will discuss next in the details.

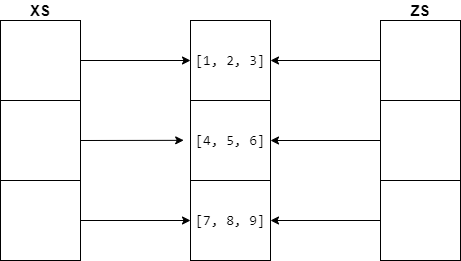

That assignment is one way of shallow copying xs to zs (check this). In layman’s terms, the object referenced by xs got copied non-recursively (i.e only the outer layer got copied and not the children to zs).

Something like this:

And that is precisely what can be observed below:

Since shallow copying does it non-recursively, only the outer object got copied in zs. Therefore, the change made by appending “outer object” to xs did not affect the object labeled as zs.

However, when the child objects got modified. The change very well affected the object labeled as zs.

What about the deep one?

Well, given the fact that we’ve already seen what shallow copy is. I believe we can now make a fair guess as to how does deep copy happen (after all it’s the opposite mechanism).

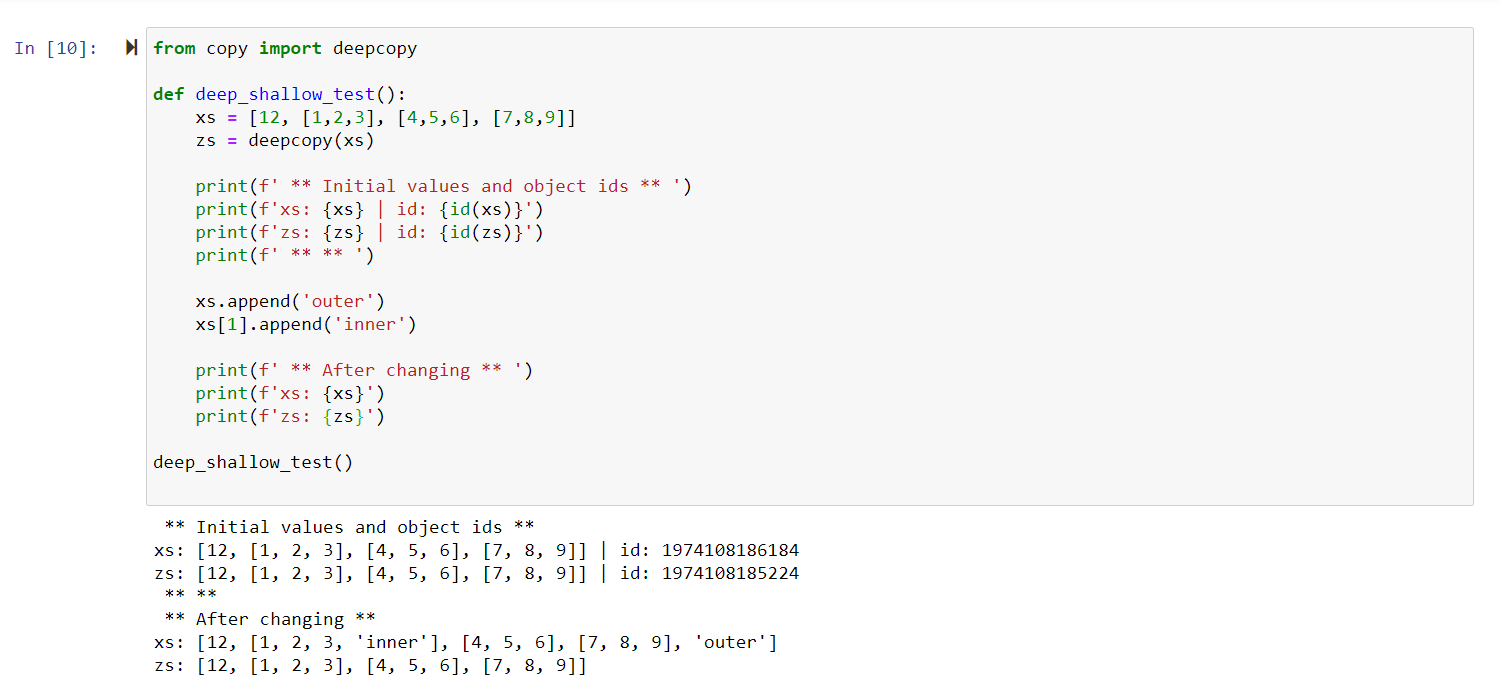

Do not worry if it isn’t clear yet. Let’s try seeing an example snippet.

Note that, xs got copied(deep) into zs, and now they are aliases to two different objects altogether. Hence the different ids. Additionally, any change made in one of the objects will not interfere with the other. That’s what the definition of deep copy tried to explain, right? It is “recursive copying”.

So, referring back to the master_list analogy made at the beginning of the post, one can easily assume that a deep copy of the master list can be passed as an argument, and called methods can safely work with it without any possible overlap.

Note: The shallow copy example, shown previously( with list() ) could have been achieved using copy from copy. i.e,

from copy import copy

zs = copy(xs)

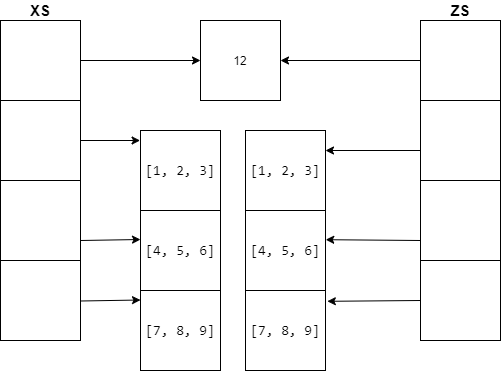

The object referencing for deep copy can be visualized as below:

One obvious questions can arise here:

why do xs and zs both refer to a single integer object 12? Even if they do, will it not make them dependent? how is then deep copy any different than shallow copy?

Well, python’s memory management mechanism is to be blamed for that.

However, that doesn’t violet the principle of deep copy in python. Just to clarify, if we change the content of xs[0] to 13 or 14. Then that would not affect zs[0] in any way.

Note that, it is possible that the inner element objects of the lists for both xs and zs are also the same. Memory management, remember!

Find more details with diagrams here.

Python documentation: here.

Inspired by: this.

featured image: Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

Thank you very much for visiting. I hope you found what you were looking for.

Good Job..Keep it up.

LikeLike